Rajasthan has the greatest diversity in vernacular residence styles, which are constructed mainly in stone. Jaisalmer has exquisite stone havelis inside the fort as well as outside it. Fine carvings embellish the sand stone with which the havelis are constructed. The more well known ones in Jaisalmer are the group of Patua havelis, Nathmalji’s haveli, and the haveli of Salim Sinh with its singular tower. Bikaner and Jodhpur also have remarkable havelis in stone. There are also the elegant havelis of Jaipur and the painted ones in the Shekhawati region, where the technique of fresco painting runs wild.

… in Rajasthan a tremendous variety of materials were used depending on local availability in the various regions – honey or golden coloured sandstone in Jaisalmer and red in Bikaner, Phalodi and Khichen. Jodhpur has lime surfaced stone and rubble painted light blue. The colours of Udaipur are white, signifying purity

The residential structures of different regions of Rajasthan have characteristic hues. While in the old city at Jaipur they are painted pink, those at Jodhpur have a light blue shade due to a tinge of colour added in the white lime coat. Further, in Rajasthan a tremendous variety of materials were used depending on local availability in the various regions – honey or golden coloured sandstone in Jaisalmer and red in Bikaner, Phalodi and Khichen. Jodhpur has lime surfaced stone and rubble painted light blue. The colours of Udaipur are white, signifying purity, as the ruling house of Udaipur did not enter into a marital alliance with the Mughals and hence did not send a Rajput princess to a Muslim ruler’s boudoir. The Udaipur ones also have the least Mughal influence and retain the unstructured amorphousness of the earlier Rajput palaces. In the villages in the Rajasthan desert, like in Barmer, due to shortage of building material, prosopis juliflora branches entwined together are used. Apart from the large variety of ceilings, of particular structural interest are the stone ceilings with ‘keystones’- flat roofs with pieces of stone in concentric circles, held together with a central keystone.

… From the street the houses look apparently congested but become surprisingly airy the moment one steps across the threshold, into the courtyard, and the noise of the street is blocked by high walls.From the street the houses look apparently congested but become surprisingly airy the moment one steps across the threshold, into the courtyard, and the noise of the street is blocked by high walls. Silavat stone carvers are credited with the construction of the Jaisalmer havelis. Of all the prominent havelis the architecture of the Patua havelis is the most complex. The five Patua brothers were from a rich trading family, resident on this earlier caravan trade route. They were dealers in zari and badla (silver and gold thread), and even money-lenders and financiers to the leading Rajput states, though their heirs ultimately shifted to Kota, Indore, Ratlam and other parts of the country. The five havelis, having six floors each, are similar in overall form yet different in assembly and detail.

Transition from the street is through raised platforms and direct view inside is obscured by screens and right-angled passages. The stone foundations rise from the basements and gradually transform into elegant columns and pilasters with a surfeit of brackets and bangaldar eaves. Niches and even lamp stands are built into the stone walls. Numerous balconies and bay windows look down on the inner lane while the common outside walls of the havelis are misleadingly bare. Windows in the rooms on all floors open into ventilation air wells (common for adjoining havelis) at different levels, and these combined with the central courtyards thoroughly circulate the air inside. The structures become more delicate towards the top where the parapets seem to bootstrap them into one whole.

… As one climbs higher inside, with more light penetrating, the sense of spaciousness increases and from the roof one gets a panoramic view of the city and the fort with the distant din of soundsFiligree work gives texture to the stone surface and water spouts interpolate the façades. The floors have narrow balconies that look down into the central courtyard. Only a few rooms still retain their rich interior adornment with gilded floral patterns, inlaid with mirrors, ivory and mother of pearl. The six levels are connected by staircases that have extended slabs at intervals for pausing. As one climbs higher inside, with more light penetrating, the sense of spaciousness increases and from the roof one gets a panoramic view of the city and the fort with the distant din of sounds. Varying patterns of light and shade at different hours of the day take the structures through a cycle of transmuted moods.

Nathmalji’s haveli was completed in 1885 and the brothers Hathi and Lallu are credited with its construction. The plan is completely different from the Patua havelis and at one time it was a unified structure, now occupied by many tenants. A pair of stone elephants and sentries outside indicate that a court minister lived here. The structure has five stories with a central and rear courtyard. The most fascinating ornamentation on its façade is a finely carved procession in stone that appears to be traveling over its eaves. The figures are small – soldiers, citizenry, caparisoned horses and elephants – and a casual visitor is likely to miss them at first. Carved windows flank the entrance, which has two cupolas in the front.

Salim Sinh’s haveli is in a fairly dilapidated state even though it was built in 1815, ten years after those of the Patuas. An elephant symbol indicates that the home belonged to a court minister. The lower portion of the structure is rather plain but towards the top it spreads out as a jahaaz mahal, ship-place, built on a five-tiered pedestal with thirty-eight cupolas and peacock motifs around it. It is said that he purposely built a high tower to embarrass the Maharawal and that there used to be two more levels that have since crumbled, called the Kanchanmahal and Rangmahal, adorned with glass mosaic work and embellishments. A structure often reflects the history of its occupation and this is apparent here – all was not well with this home and Salim Sinh died in 1827, poisoned by his wife.

… It is obvious that during this region’s heyday the residents embarked on a competitive fresco painting spree and not a square inch is left bare on the exterior of some houses. The themes include the familiar legends and epics – Dhola Maru, Krishna legend, Mahabharata, Ramayana – interspersed with cars, trains, airplanes, ships, brass bands, Ganeshji, Lakshmi (the goddess of wealth), floral and geometric patterns.On the edge of the Rajasthan desert, in the Marwar region, is the area of Shekhawati with its painted havelis. The Shekawati havelis – courtyard houses – are made of stone and rubble, built with lime, stucco work and ornamental frescoes and paintings. Shekhawati is named after Rao Shekhawat, a cousin of the Jaipur Kachhwaha rulers, who declared independence from them in 1471. Shekhawati comprises of the present districts of Sikar, Jhunjhunu and parts of Churu, the more important towns being Ramgarh, Fatehpur, Lachhmangarh, Jhunjhunu, Chirava, Churu, Mahansar, Mandawa, Nawalgarh, Surajgarh and Malsisar. The main residences are of Rajputs of the area and rich merchants, who are now some of the biggest business houses of the country, their houses here now unoccupied.

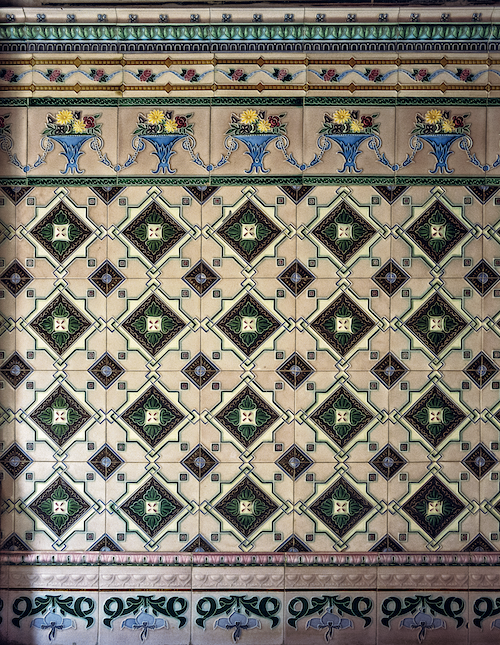

It is obvious that during this region’s heyday the residents embarked on a competitive fresco painting spree and not a square inch is left bare on the exterior of some houses. The themes include the familiar legends and epics – Dhola Maru, Krishna legend, Mahabharata, Ramayana – interspersed with cars, trains, airplanes, ships, brass bands, Ganeshji, Lakshmi (the goddess of wealth), floral and geometric patterns. Homage to the British rulers is evident in the scenes of the durbar of King George V and portraits of Queen Victoria. With the opening of other trade routes business declined in this region and the leading families are now all in metropolitan cities like Bombay, Calcutta or Delhi, and make annual vacation pilgrimages to their ancestral homes. Some of the structures are grand and have up to five or six symmetrical courtyards. For the paintings natural pigments and dyes were used earlier and then replaced by synthetic paints. The fresco buono technique was used by the painters who were a branch of the potter caste.

… What makes the Gujarat havelis extremely varied in detail is that there were both Hindu and Muslim artisans and there was healthy rivalry between them

Beyond Rajasthan are the marvellous havelis of Gujarat. The structures are timber bonded vertically and horizontally, the teak timber linking up with other elements like columns, jambs and windows, forming the ribs of the structure. What makes the Gujarat havelis extremely varied in detail is that there were both Hindu and Muslim artisans and there was healthy rivalry between them. The door frames, columns, capitals, brackets and wall panels are covered with intricately carved motifs that are geometrical or represent life forms, depending on their styles, broadly Muslim or Hindu. The carvings include floral scroll-work, animals, birds, human figures, deities and geometrical designs. The temples of certain Hindu sects are also called haveli and have well-preserved stone and wood carved interiors, like those of the Swaminarayans’ at Ahmedabad and the derasars of the Jains.

The havelis of Gujarat appear to have reached their peak around the end of the last century and a company was also incorporated to make and export residential artifacts and furniture to European customers. This company, Mulchand Hathisinh Brothers, at one time had 125 full-time artisans, but by 1902 had only a dozen or so left. A splendid wooden haveli façade had specially been built by the government for the Colonial and Indian Exhibition held at London in 1886. After the show it was brought back and is now exhibited in the museum at Calcutta (illustrated in this work). For Gujarat (then part of Bombay state) it was a period of excellence in workmanship in wood within other spheres as well – ship building, block making, marquetry and lacquer work. Wooden items for domestic use like dowry chests (damachia, pitara, majoos), cupboards (navkhania), water pot stands (paniara) and swings (jhula) were also intricately carved. Community items were also ornately carved, like the parbadi or pigeon house in the town square. The Suthar caste provided the carpenters and included the functional sub-castes of Vaishya, Mevada, Pancholi and Gurjar.

… Since areas of Gujarat are semi-arid the courtyards often had a tank underneath to store rainwater… Rain-water from the roof was saved in an underground tank under the courtyardIn a Gujarati haveli the plinth of the structure is normally raised. The main entrance door is of solid wood fabrication and divided into rectangular panels, plane or engraved. In the Hindu homes, on the top of the door-frame, preside the deities of Sri Ganesh or Lakshmi amidst engraved floral decoration. Visual transition is through embellished wood framed windows, small at street level (within an iron jali or screen for protection) but expanding at higher levels into bay windows and cradle balconies. There is more ornamentation towards the top of the structure and the architraves and rafters that prop the upper stories are profusely carved with friezes and linear designs. The brackets and capitals are also densely carved which adds a certain delicacy to their inherent strength. The motifs range from inanimate objects like trees, vines and leaves to the perennial peacock, parrot, horse and elephant. Rosettes relieve plain areas in the wood. Round columns become square at the top to allow a good fit for the beams and struts. The finished wood is given a coating of oil, sometimes with the addition of mineral earth colours, which is renewed before festivities and marriages.

The courtyard of the Gujarati haveli varies from a single small one to a number of larger ones. Since areas of Gujarat are semi-arid the courtyards often had a tank underneath to store rainwater. The urban havelis of Gujarat belonged to traders and merchants and hence the courtyard never had to function as an area of agriculture related activity. In the Muslim haveli design of Patan, restrictions on available space constrained the courtyard into being a narrow opening, the sides of which served as the sitting area. Moreover, instead of a zenana in the horizontal plan, the women’s quarters in the Patan havelis were on the upper floor and wood-screened openings were provided at that level around the court space from where the women could communicate, without being seen, with people below.

… Big cities like Ahmedabad had pols (settlements of one particular community) with a cluster of traditional houses with carved façades and chabutras – pigeon posts or towers. The pols had areas for artisans and wells

Big cities like Ahmedabad had pols (settlements of one particular community) with a cluster of traditional houses with carved façades and chabutras – pigeon posts or towers. The pols had areas for artisans and wells. Hindu and Muslim features of wood carving differs in the sense that while Hindus artisans could carve whatever images and designs they wanted to, the Muslim style of wood carving could not depict living beings or creatures. In both the styles, however, wooden carved columns rest on carved stone bases. Rain-water from the roof was saved in an underground tank under the courtyard. Swings were there for relaxing and creating a breeze on hot summer days, and grilled doors give security with ventilation. Patan Muslim and Hindu houses had a vavdan or wind catcher to channel the breeze from the roof of the house to the levels below or provide indirect circulation due to a venturi effect. The timbering could be half or full.

… Lippankaam, mud decorative work with small mirrors embellishes the inside of these hut. The interior also has clay cupboards with wooden shutters for storing food grains

Kachchh in western Gujarat, in its Banni pasture land has circular bhungas or huts made of mud, clay and thatch with working area in-between covered by shelter of branches of prosopis juliflora, the main shrubby tree in the desert region. Lippankaam, mud decorative work with small mirrors embellishes the inside of these hut. The interior also has clay cupboards with wooden shutters for storing food grains. The conical roof is of woven branches or wood flats tied with twine and packed with brushwood. The Banni huts are of Muslim herders while the Hindu Rabari mud huts are there in other parts of Kachchh, including the famous village of Tunda on the coast.

During the British days and for some years after, Gujarat was administratively part of Bombay state, now Maharashtra, where the wada is the vernacular equivalent of the vernacular courtyard house. The term wada was also used in Gujarat earlier because of the historical links between the two states and the fact that the ruling Gaekwad family of Baroda was formerly Maratha. This form of residential architecture of the Maratha aristocracy is, however, distinct from the Gujarati haveli style and began under the patronage of the Peshwas from the early eighteenth to the nineteenth century. The material used is carved wood bonded with masonry or stone, though the proportion of wood is less than in the Gujarati haveli. The wada homes do not exist in as large a number as the havelis of Gujarat.

Compared to the Gujarat haveli, in a wada the columns are usually tapered and have wooden arcades in between, carved ornately with floral and animal designs. The façades are plainer and the courtyards are larger, with a well in a corner, surrounded by living and functional rooms. The main entrance has an image of Ganeshji engraved on it. A wada has a room for religious ceremonies and functions called the diwankhana, which is on the first floor. Alternatively a corner at the end of a hall is partitioned for this purpose and an image of the family deity installed in an ornamental niche in the wall. A false ceiling of wood panelling is engraved with meandering floral patterns and coloured glass lamps are suspended from it. The overall colour scheme is bright but with little ornamentation outside.

… it is interesting that some wada homes were built as small pleasure palaces, having symmetrically laid out garden plans and fountains, with Persian wheels for filling the overhead tanks, like the magnificent one at WaiIn some wadas, the inside plaster walls facing the court are adorned with monochromatic frescoes in earthen colours of deep red or ochre. The themes of these paintings are illustrations from epics and legends. This colouring technique is known as abashi and the painters belong to the Jingar community. Functional niches with stucco work are built into room walls in clusters and glass paintings adorn the sitting areas. Considering that the Peshwas are Brahmins, it is interesting that some wada homes were built as small pleasure palaces, having symmetrically laid out garden plans and fountains, with Persian wheels for filling the overhead tanks, like the magnificent one at Wai.

The tribal areas of Gujarat have huts that use the broad teak leaves over straw thatch. Woven split bamboo walls with a coating of mud are made by artisan classes who even today weave baskets, or by the tribals themselves. The mud surface is finished with a coat of dung. Tiles were made locally by potters but are now being replaced by factory made tiles. The huts of the Rathwa tribals are adorned with colourful pithora wall paintings while those of the Warli tribes have drawings in a geometrical manner made with rice paste 🟥