A vast compendium of architecture design exists in India – that of vernacular or traditional residential architecture, whether of the near past or earlier historical periods.

… This situation is not being helped by uniform reinforced concrete specifications for mass housing schemes of governments which often result in uncomfortable dwellings, ill-suited to their localesIt is, however, virtually untapped and fast disappearing. A stage has come that future generations will not even know how their ancestors have lived and the visual and technical details of such structures would fade into oblivion.

India’s diversity of people is correspondingly matched by a great range in its vernacular architecture – urban, rural, tribal huts and other shelters – influenced by different religious, social and climatic requirements, as well as made according to locally available building material. However, no sustained attempt has been made to visually record and analyze this heritage that is fast disappearing, though periodic attempts to encourage it have been made by discerning and concerned architects and organizations. This situation is not being helped by uniform reinforced concrete specifications for mass housing schemes of governments which often result in uncomfortable dwellings, ill-suited to their locales.

… Vernacular residences of the rest of the country have hardly been commented upon, leave alone recorded and evaluated for elements that are relevant even today. No worthwhile data exists regarding them so far, statistical or visual

Only the opulent palaces of India’s former Maharajas have had some material published about them, but most of these were built with foreign influences in the second wave of palace building under the reign of the British rulers, compared to the more indigenous palaces before. Ironically, India’s erstwhile Maharajas could build elaborate European styled and Indo-Saracenic palaces in their glory only when they were under the rule of the colonial British rulers. Vernacular residences of the rest of the country have hardly been commented upon, leave alone recorded and evaluated for elements that are relevant even today. No worthwhile data exists regarding them so far, statistical or visual.

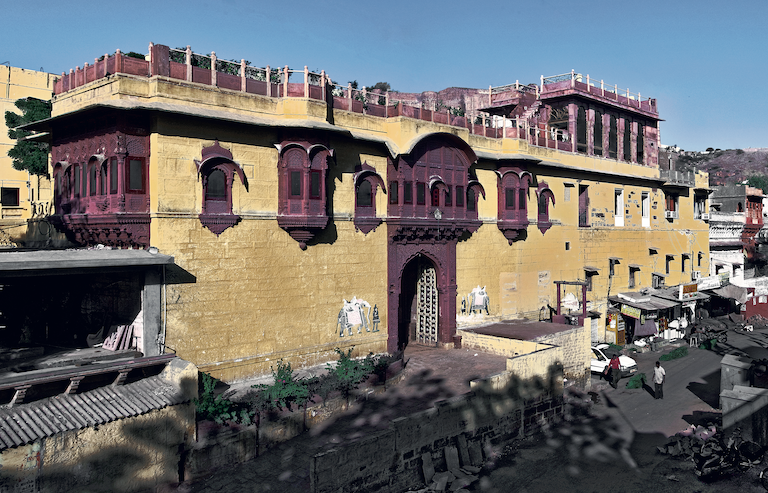

The qualities of traditional Indian residences are considerable. Indigenous styles provide sustainable solutions for housing and blend with their surroundings. Their scale as well as character is in tune with local topography and physical features of the land. The materials used (stone, bricks, mud, wood, bamboo and thatch) are generally local and easily merge with the surroundings. The spaces are functional according to the local ethos, cultural values, customs and beliefs of the community and there is repetition of these basic design units to create architectural harmony. These parameters are not absolutely rigid and status considerations could also generate demand for non-indigenous materials, like the wooden havelis of Gujarat, though social considerations of design in relation to designated areas and spaces were still adhered to. Some conundrums still exist regarding Gujarati haveli design elements like the door tollas (saddle-pieces in the corners of door frames) that appear to have links with the Coptic churches of Abyssinia, perhaps through trade. It is not without reason that some earlier town planners in India like Patrick Geddes were sociologists also.

… The need for studying and analysing traditional houses, dwellings and shelters of India is not just based on nostalgia but also because of the fact that they are great design resources for appropriate technologies even today

There was also considerable sharing of design elements between vernacular domestic architecture and the great monuments in the sub-continent, like the simple bangla hut form of eastern India being used in brick temples and even in monuments in north and other parts of India as bangaldar vaulted roofs, along with other details related to cornices, clerestory windows, etc. Local religious connotations played a great role in the borrowing of styles between bangla village huts and the brick temples since village deities were kept in thatched huts in villages. Even in the vihara cave architecture of India, though the material is stone, wooden-type beams and rafters were carved in the stone ceilings of the caves, showing interlinking of the stone elements of the monumental caves with wooden designs used in residential buildings. The complete range of architectural features can be found in vernacular architecture, from Hindu beams and corbelling to Islamic domes and arches. In fact, in Bijapur the houses used by Adil Shah’s generals are still in active use even today, so sturdy was their construction hundreds of years ago!

The need for studying and analysing traditional houses, dwellings and shelters of India is not just based on nostalgia but also because of the fact that they are great design resources for appropriate technologies even today – their basic plans, living spaces and circulation paths, light and heat entry points during different times of the day and seasons (thus keeping the building cool in summer and warm in winters) – all based on locally available skills and materials. Some are green buildings in the modern sense of the phrase and have rainwater harvesting methods and energy conservation features built-in, with air circulation to keep them pleasant in summers, in the absence of air-conditioning.

… Vernacular structures are superb examples of cost-effective, appropriate building design and construction technology and were innovative in plan and embellishment. On the whole they made up for truly sustainable human settlements with an obviously great quality of life for the inhabitantsThe typical features of indigenous structures are more eco-friendly and energy saving than modern construction. Adobe walls keep structures many degrees cooler than street temperature in the hot summers. The courtyards of havelis serve as temperature regulators and help in the circulation of fresh air inside the building, aided by wind scoops and convection towers. An introverted structure, as in havelis, provided for privacy and insulation against noise from the streets, while optimally placed chajja fenestrations and jharokha balconies related the interiors to outer space and a stepped threshold platform marked a clear transition from the street. Easy circulation spaces inside with a courtyard made for considerable comfort. In some parts of India, even today, granaries are constructed separate from the main house to reduce exposure to disease and vermin.

Vernacular structures are superb examples of cost-effective, appropriate building design and construction technology and were innovative in plan and embellishment. On the whole they made up for truly sustainable human settlements with an obviously great quality of life for the inhabitants. Now with lack of patronage the popularity of such buildings has declined considerably and the related construction skills too are dying. The urban legal framework, too, lacks clarity as to the role of the State for the preservation of such structures or for the promotion of their worthwhile features and, in fact, new introverted haveli style buildings can not be made with zero set-off from the road.

The objective of this work is to bring out reference material on vernacular residences for the whole of India, visually analysing the best examples of such traditional residential architecture in the country. The scope of this work has been limited to vernacular architecture of India, which means the traditional residences styles of its people and not its monuments and palaces. It is for the first time that such an effort has been undertaken to document vernacular architecture in the entire country, from the Himalayas to the coastal regions, east to west and from traditional residences of the elite to the unique dwellings and huts of secluded tribals.

… While considerable stress is being placed on achievement of quantitative figures by governmental institutions engaged in housing activities, design features seem to be getting lesser importanceThis reference material will serve as a resource bank not only for individual architects and planners but also for housing projects of governments. Many residence typologies of the country have already disappeared and an effort has been made to search for visual clues in the ancient murals of Ajanta caves as well as in the great sculptural traditions of India and highlight them.

While considerable stress is being placed on achievement of quantitative figures by governmental institutions engaged in housing activities, design features seem to be getting lesser importance. This is not only the case for aesthetics but even for functional characteristics, like use of appropriate technologies, energy conservation and other features for efficiently enhancing qualities of life in general in human settlements – both urban and rural. No doubt limitations of land and resources are there that constrain such indulgences but an effort in using traditional good practices can certainly be made.

The photographs taken by the author and used in this book date from the nineteen-seventies onwards and use has also been made of some historical black and white photographs from the collections of the Anthropological Survey of India. By and large, no relevant or interesting traditional residence, vernacular style, structure or construction technique that deserves to be covered has been left out and different styles within the same state have been covered.